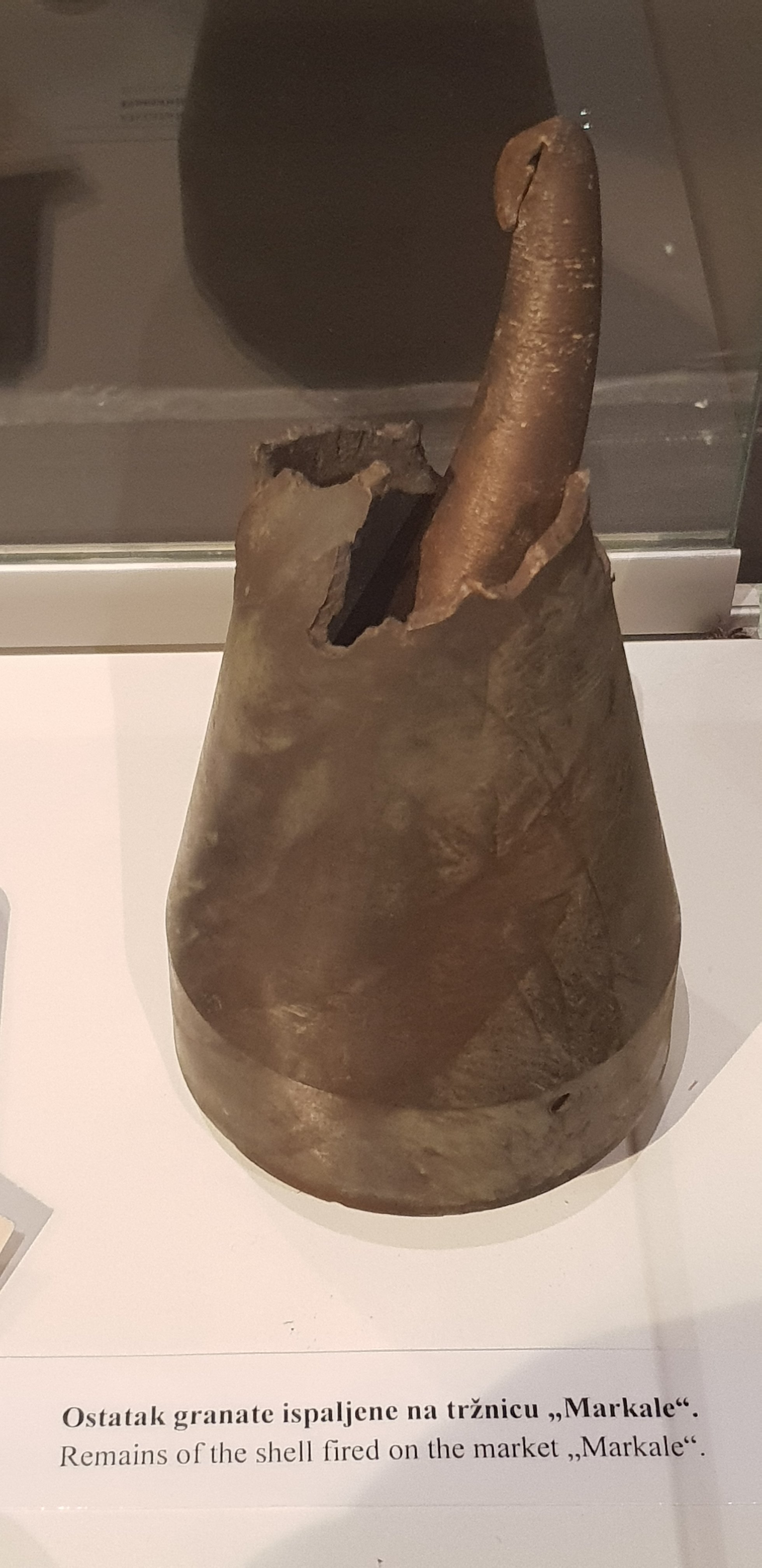

At 10 I was perhaps the first visitor to the museum, and spent some time talking with a docent. He is a middle-aged Bosnian Muslim who has lived all his life in Sarajevo. Then he was here during the seige? Yes, he says. It is hard in Bosnia. It is a multi-cultural society. His best friend is Serbian, and lives in Seattle. He left during the war. His second best friend is Croatian and lives in Zagreb. It is hard. What is hard? He visits his friend in Zagreb perhaps once a month. It is hard. What is hard? Is it hard to be a Muslim in Zagreb? Yes, he says. They do not like Muslims in Zagreb. I tell him it was very strange in the United States after September 2001. There was a great deal of fear, and somehow it made sense to Americans to attack Afghanistan and invade Iraq even though most of the 9/11 hijackers were Saudi. To many Americans all Muslims in the world are the same. What would he like Americans to know about Muslims in Bosnia? He smiles. Bosnian Muslims are not like Muslims in Afghanistan, he says.

At 10 I was perhaps the first visitor to the museum, and spent some time talking with a docent. He is a middle-aged Bosnian Muslim who has lived all his life in Sarajevo. Then he was here during the seige? Yes, he says. It is hard in Bosnia. It is a multi-cultural society. His best friend is Serbian, and lives in Seattle. He left during the war. His second best friend is Croatian and lives in Zagreb. It is hard. What is hard? He visits his friend in Zagreb perhaps once a month. It is hard. What is hard? Is it hard to be a Muslim in Zagreb? Yes, he says. They do not like Muslims in Zagreb. I tell him it was very strange in the United States after September 2001. There was a great deal of fear, and somehow it made sense to Americans to attack Afghanistan and invade Iraq even though most of the 9/11 hijackers were Saudi. To many Americans all Muslims in the world are the same. What would he like Americans to know about Muslims in Bosnia? He smiles. Bosnian Muslims are not like Muslims in Afghanistan, he says.

Last year a group of US engineers resisted the Trump Administration and publicly vowed they would not work on any registry of Muslims in the US. The statement was a very clear and simple one. It referenced, along with other historical acts of ethnic cleansing, Bosnia. Signing on was an easy automated process. I signed and posted this to my Facebook page, posted it on LinkedIn, and e-mailed it to a number of high tech acquaintances. I got not one response. I watched the roster of signatures for the next few weeks. No names that I knew appeared.

Rock on, Goethe Institute!

Rock on, Goethe Institute!

This corner was the first place I headed to when I arrived yesterday.

This corner was the first place I headed to when I arrived yesterday.

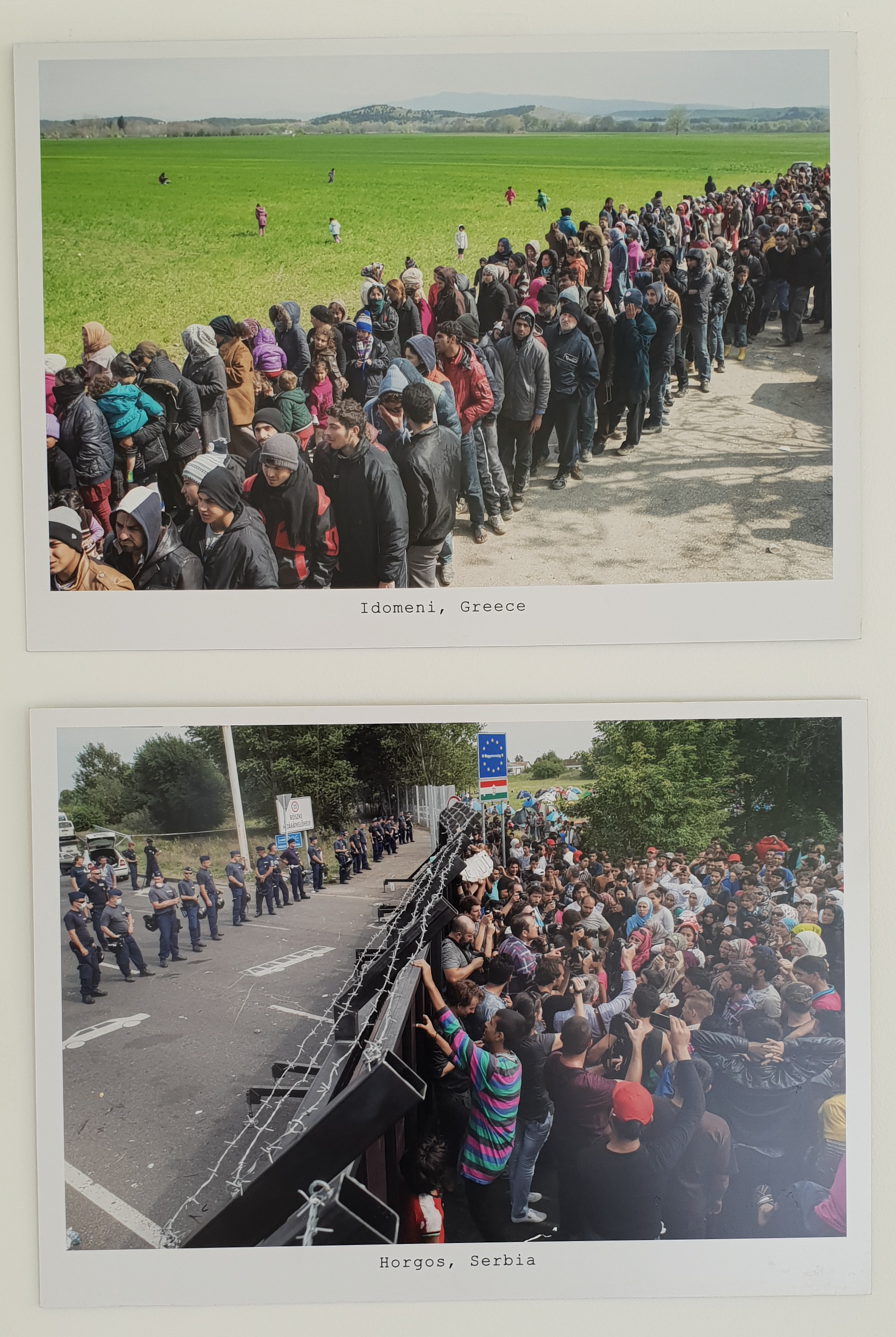

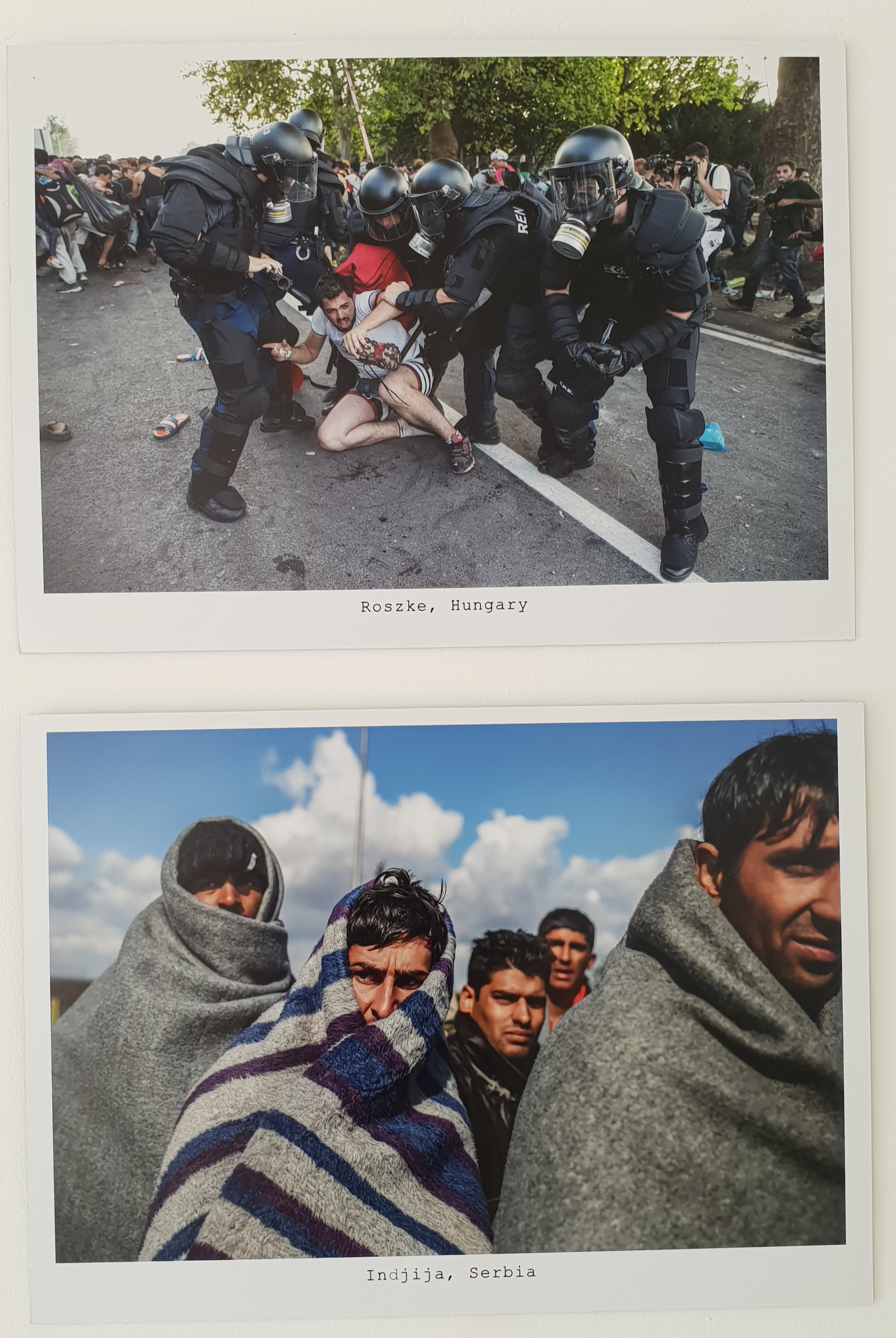

The collection of refugee photographs was large and striking. Needless to say I thought of the different refugees I met in Berlin.

The collection of refugee photographs was large and striking. Needless to say I thought of the different refugees I met in Berlin.

I was in the museum’s galleries perhaps 45 minutes. During that time several groups of tourists, of different nationalities, came and went. A Chinese group, with a Bosnian interpreter, very loudly passed through with much taking of photographs including of tourists in front of exhibits. When I headed out through the entrance I was again the only visitor. My interlocutor was talking to a friend who approached me with his pitch to drive me to the Tunnel Museum. I have a car, I say. Everyone has a car! He dismisses this information as unimportant. With him, and his car, I get him as a guide, and this is his city. And he knows this tunnel – he escaped through this tunnel to Italy. He lived in Italy for many years before returning to Bosnia. What would he like Americans to know about Bosnia? He can show me the tunnel, and the city. This is his city. He knows this city. Yes. I am curious what he would like Americans to know about Bosnia. Him? He eyes me suspiciously. Yes. What would he like Americans to know? Americans, he says, America is very fast. America is ok to visit for a week, but he would not want to live there. It is very fast. Italy, now Italy and Bosnia is where his life is. Italy and Bosnia are good places to live. Having found I am not going to hire him he has lost interest in me. I don’t blame him. Entertaining me is a waste of his time.

On my way out I speak again with the museum employee, who is very engaging. While I was inside other tourists came, I say. Yes, he agrees. They seemed to go through the museum and go out again. Yes, he says. What is my question? They seemed to go rather quickly, I point out. Is that normal? Yes, he says, it is normal. But it seems to me you can’t really see things if you go quickly, I ask. Yes, he smiles.