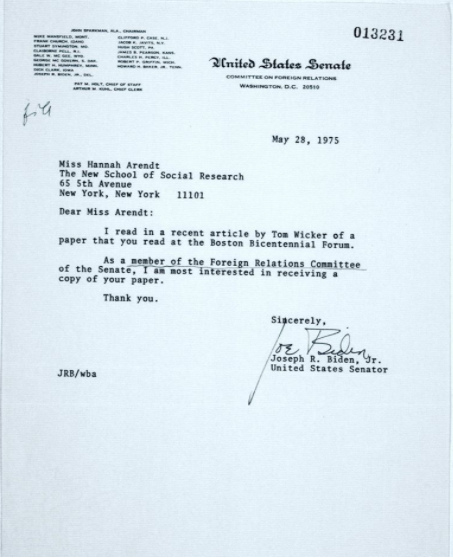

Hannah Arendt Center, Bard College:

Tom Wicker’s piece, NYT 25.05.1975:

BOSTON‐The approach of the Bicentennial year is causing a good many Americans to search for the “deeper causes” underlying the recent collapse of American foreign policy and the economic and social disarray at home‐“precisely because,” Hannah Arendt said here the other day, “people are aware of the fearful distance that separates us from our extraordinary beginnings.”

Yet, Miss Arendt warned in a remarkable paper she read at the Boston Bicentennial Forum. “All speculation about deeper causes returns from the shock of reality to what seems plausible and can be explained in terms of what reasonable men think is possible. …. if it is in the nature of appearances to hide ‘deeper causes,’ it is in the nature of speculation about such hidden causes to hide and to make us forget the stark, naked brutality of facts, of things as they are.”

Miss Arendt, the noted author of “Eichman in Jerusalem” and now professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research, returned again and again to this theme, the difference in things as they are and things as they can be made to seem—the difference, for example, in “our … outright humiliating defeat” in Vietnam and what Americans had been led to believe would be “peace with honor.”

The American tendency to substitute an image or a phrase for an unwanted reality, she said, had grown to “gigantic proportions” because the techniques of public relations had been borrowed from their usual function—“to help distribute the merchandise” —and had been “permitted to invade our political life.” Thus, she argued, careful reading of the Pentagon Papers disclosed that the Vietnam war had been waged for no real or tangible purpose but solely because of “the needs of a superpower to create for itself an image which would convince the world that it was indeed the mightiest power on earth.”

In the end, therefore, when defeat became inevitable, the entire American Government “strained its remarkable intellectual resources on finding ways and means of how to avoid admitting defeat and keep the image of the ‘mightiest power on earth’ intact.”

Thus, Miss Arendt said, the Ford Administration first attempted to blame the Democratic Congress, variation on “the stab‐in‐the‐back legend, generally invented by generals who have lost a war.” That failing, President Ford, “forgetting for the moment that he had refused to give unconditional amnesty, the timehonored means to heal the wounds of a divided nation,” urged the nation not to look back, to forget the past, to open a new chapter in its history.

This led Miss Arendt to the acid observation that Mr. Ford’s tactic was a “return to the oldest methods of mankind to get rid of unpleasant realities‐oblivion. Not amnesty but amnesia will heal all wounds.”

Primarily, however, she was arguing the arresting case that “imagemaking as global policy,” while new in “the huge arsenal of human follies,” was essentially an American version of “big lie” techniques devised in Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. There, she said, lying was guided by ideology and backed by terror; here, it has been directed at creating images and bolstered by “hidden persuasion” and the manipulation of public opinion‐“the seemingly harmless lying of Madison Avenue.”

The totalitarian governments dug “giant holes in which to bury unwelcome facts and events, a gigantic enterprise which could be achieved only by killing millions of people who had been the actors or witnesses of the past.…” And for Miss Arendt, the most serious consequence for Americans of these “terrible disasters” in Europe was that “this form of criminality with its bloodbaths has remained the conscious or unconscious standard by which we measure what ie permitted or prohibited in politics.” Public opinion, that is, has been dangerously inclined to accept anything short of murder as “just politics.”

Nor was Miss Arendt sanguine that Vietnam and the Watergate revelations had changed things. The Watergate culprits, she noted, had been overwhelmed with rich offers from publishers, television, campuses; and she suggested that these offers “reflect the market and its demand of ‘positive images’‐that is, its quest for more lies and fabrications, this time to justify the cover‐up and to rehabilitate the criminals.”

As for the Mayaguez incident, she could only hope that it represented at last “the nadir of self‐confidence, when victory over one of the tiniest and most helpless countries on earth could cheer the inhabitants of what only a few decades ago really was the mightiest power on earth.”

No short article could possibly do justice to the extraordinary range and richness of Miss Arendt’s paper. But its main theme, only sketched here, demands her own conclusion: “When the facts come home to roost, let us try at least to make them welcome, let us try not to escape into some utopias—images, theories, or sheer follies. It was the greatness of this Republic to give due account to the best and to the worst in men, all for the sake of Freedom.”

Home to Roost_ A Bicentennial Address _ Hannah Arendt _ The New York Review of Books